Amid the green pastures and historical placards of the last active Shaker community, a trio of believers is keeping the faith. Monica Wood paid a visit to the Shakers of Sabbathday Lake.

By Monica Wood

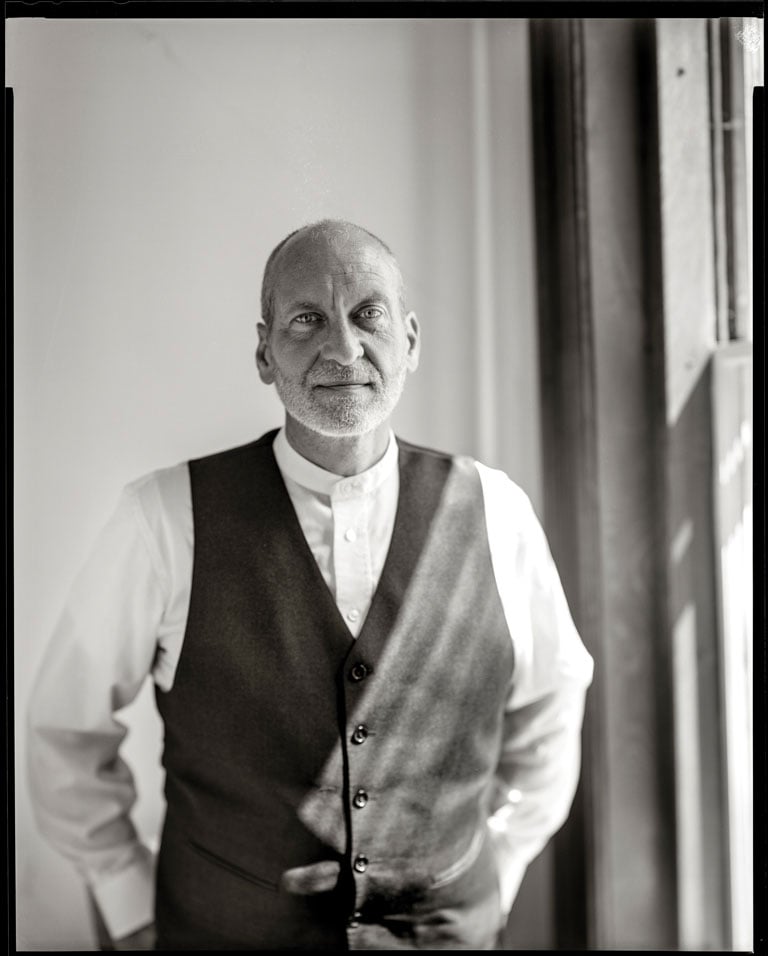

Photographed by Séan Alonzo Harris

From our October 2014 issue

[cs_drop_cap letter=”P” size=”5em” ]aused at the top of the road overlooking the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, I recall a line from “Simple Gifts,” a well-known Shaker hymn written in Maine in 1848: “And when we find ourselves in the place just right // it will be in the valley of love and delight.” I step out of my car and breathe the immaculate morning air. From across the summer-lighted fields, I catch the song of the veery — a bittersweet, swirling call. How easy it would be in this lush, peaceful idyll to accept the mistaken myth of Shakers as an ethereal or monastic people, somehow separated from this world.

When I reach the small, tidy village, I find a dozen buildings, all of them wooden, painted white, and decidedly earthbound. The bucolic scene hums with enterprise — “simple” doesn’t always mean “quiet.” Sheep and cows bellow from their pens, a door somewhere rattles open, and several cars of tourists are already pulling in. There are buildings to paint and fences to mend. Sabbathday Lake is home to the world’s only three remaining Shakers — Brother Arnold Hadd, 57; Sister June Carpenter, 76; and Sister Frances Carr, 87 — and with such a small nucleus, the community relies on a large and loyal group of volunteers to keep pace with the monumental work of running a farm and historic site.

The Sabbathday Lake Shakers settled on this rolling spread near New Gloucester in 1783. Today, they lease some of their farmland and all of their apple orchards. They raise cows for sale and bring in professional shearers for the sheep. They keep bees and grow vegetables and herbs. With a museum, gift store, and research library to run, they employ four people full time and as many as 12 in the summer. They manage and train a stable of volunteers, many of them friends and family who come back year after year. (Brother Arnold’s sister, for instance, helped plant this year’s garden.) They respond to an ever-surging tide of queries — from students, researchers, and eminent museum directors — and their online presence presumably comes with the same tech headaches that bedevil the rest of us. Sunday services are open to all and attract as many as 50 worshippers during peak tourist season.

Simply put, the Shakers are busy.

“Come on, Houdini! Move it, Snuffles! Let’s go, children!”

That’s Brother Arnold, urging a bleating band of 42 sheep into the barn for their breakfast. He’s trailed by two feral cats, since along with his cell phone and muck rake, Brother Arnold carries a fragrant, open can of Friskies. What follows is an astonishing daily circus act of hand feeding, pan feeding, stall mucking, and hay pitching. In his polo shirt, work pants, and rubber boots, Brother Arnold is a one-man band of barn chores, hyper-focused and utterly composed, his demeanor a reminder that in the Shaker religion, work and worship are deeply twined.

Believers hold that God is both male and female, that Jesus was the first to be wholly imbued by the Spirit and that the second was the Shakers’ foundress, a working-class spiritual seeker called Mother Ann Lee. While they don’t reject the divinity of Jesus, they do believe in an “indwelling” Christ: God made manifest in all of us, in the smallest gesture of the smallest day. Shakerism is not, as Brother Arnold puts it, a “part-time religion” to be practiced on Sundays. Shakers remain celibate in imitation of Christ. Men and women live separately and use separate entrances to their meetinghouse, although the Shakers have always preached gender equality since their eighteenth-century beginnings, when this was a radical and even heretical notion.

Equality, social justice, and pacifism still figure deeply into the Shakers’ daily attempt to live the life of Christ, and every aspect of Shaker life embraces two essential principles: unity and simplicity.

In the spirit of these principles, Brother Arnold is feeding six monstrous cows — Scottish Highlands, huge and shaggy, like woolly mammoths — all the while being tailed by Teddy, an endearing brown Romney sheep that gets to lord it up while his flockmates stay penned.

“Teddy’s small and new and the other sheep keep ramming him,” he explains. His speech is brusque, his movements quick and purposeful. I follow him to a back room where Thomas the cat, though skittish and feral, submits to a petting from his benefactor and, even more impressively, a full work-over with a flea comb. Brother Arnold: cat whisperer.

Though a fool for critters, Brother Arnold is no softie. Wiry and intense and blessed with ferocious energy, he fills multiple roles at Sabbathday Lake: animal tender, gardener, cook, historian, trustee, manager, and spokesman. It isn’t hard to see in him the stubborn 16-year-old who once argued with a tour guide during a family trip to a Shaker historic site in 1974. The young Arnold, who grew up Methodist in Springfield, Massachusetts, fired off a righteous note to the Sabbathday Lake community after his visit, demanding confirmation that one Brother Ricardo, whom the tour guide had insisted was a “lifelong” Shaker, had in fact left the community for a time. A small point, sure, but Arnold’s grandmother had told him of a lapsed Shaker by that name who’d once lived next door. The return letter, which proved Arnold triumphantly right, included an invitation to visit from a Brother Ted, who’d been Brother Ricardo’s protégé.

And so it came to pass that the cheeky teenager from Springfield met his mentor and his match, a spiritual man who changed the course of Arnold’s life. Brother Arnold speaks of their relationship with reverence and humor. “I wavered for years, but Brother Ted was a persistent man. Finally, he said to me, ‘Listen, you’ve been up here over and over again. Make up your mind already!’” Arnold did make up his mind, at age 21, when he was darned good and ready.

[cs_drop_cap letter=”T” size=”5em” ]hirty-six years later, the rest of the Brothers are gone. Brother Arnold introduces me to the Sisters with whom he now shares a life and a home. We assemble in the empty dining hall of the five-story Dwelling House, where as many as 183 Shakers once ate, slept, and worshipped. The large, airy room contains little but black-and-white portraits of Shakers past and the well-made tables and chairs for which Shakers are renowned. As we settle in, Brother Arnold’s brusqueness falls away, replaced by a wry humor well-suited to the caprices of farm life.“How many Sisters does it take to change a light bulb?” he asks, breaking the ice.

Sister Frances and Sister June chuckle.

“None,” says Brother Arnold. “They wait for a Brother to do it.”

Sister Frances grins at him from across the table. “Now, Brother,” she admonishes, “that was kind of mean.”

Impossibly youthful at 87, Sister Frances is truly the last of a kind, since she dates back to a time when Shakers maintained their numbers by taking in orphaned children. (Their ranks swelled, for example, during the mass bloodshed of the Civil War.) Raised in Lewiston, little Frances arrived at Sabbathday Lake in 1937, a 10-year-old dropped off with her younger sister by the pair’s poverty-stricken mother, who’d already given up two other children to the Shakers. What she remembers most isn’t the heartache of being abandoned, but her first evening meal: a hot dog, which posed quite a quandary for a devout Catholic child forbidden to eat meat on Fridays.

“I didn’t know what to do,” Sister Frances recalls. “Should I eat it? Should I pretend I’m ill?” Her sister, who loved to eat, gobbled the hot dog without moral reflection. But Sister Frances dug in her heels: She fibbed her way out of that first forbidden food, continued to cross herself in the Catholic fashion, and took an instant dislike to Sister Mary, the children’s caretaker.

The next few years were turbulent — imagine the sorrow of a motherless child — and Brother Arnold implies that Sister Frances might have been a hellion. “Oh, I was a handful,” she admits gleefully. She defied Sister Mary’s orders, threatened to forgo her prayers, filched a bucket of maple sugar, and once exited through a window rather than a door. The memories make her laugh today, and I see something of that girl in her crisp white blouse, her still-thick hair, and her warm, impish, chatty personality.

“But I did love the kitchen,” she recalls, gesturing behind her, where we hear a clatter of pans. “I started out as a ‘sink girl,’ peeling potatoes and that sort of thing, then I started cooking later on.” Sister Frances eventually found serenity with the motherly Sister Mildred, who took the girl under her wing and trained her as a teacher. She learned to love and abide by Mother Ann’s motto: “Hands to work and hearts to God.”

When she came of age, she elected to stay. Because her siblings decided “to go to the world” — as most children eventually did, with the community’s blessing — Frances felt a measure of pity for the Shakers, who’d invested so much in the children remanded to their care. But she didn’t join out of pity. In Sister Mildred she saw someone who lived the Shaker life “more completely” than anyone she’d ever known, and her example readied Sister Frances to make a lifelong commitment. She signed the Shaker Covenant with little ceremony in the presence of her mentor.

Sister June, by contrast, joined the Sabbathday Lake community as an adult — a means of recruitment that today represents the Shakers’ only hope of survival. A collections librarian from Massachusetts, she visited the village in the late 1980s after reading about it in Down East. (She’s still a subscriber.) At first glance, she felt a spiritual call.

“In the driveway,” she says, “looking at the Dwelling House, I felt I should be living there.” After several extended visits to volunteer at the Shaker library, she joined at age 50 and for years acted as cataloguer for the Sabbathday archive — the largest collection of Shaker materials in the world.

Sister June says she “feels close to God all day long here,” especially upon waking. When she opens her eyes in her sleeping quarters, she asks him for a good day. At night, as she falls asleep, she thanks him for fulfilling that wish.

Dressed in a purple bib-front Shaker dress, the late-life convert glows with curiosity despite an intense shyness that she quietly admits. “I ask God to help me socialize.” She looks up — the dining room is flooded with midday light— and Sister Frances jumps to her defense: “But oh, she’s come so far! She used to disappear when we had guests, but now she joins right in.”

“And she’s a champ at Trivial Pursuit,” adds Brother Arnold, smiling with the resignation of a man who’s lost a game or two.

Sister June shrugs. “I read a lot, that’s why. I’ve always loved reading.” Raised on Louisa May Alcott, Sister June counts Little Women among her most beloved books. Together, we recite the first line: “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents!” When she smiles, her round face takes on the blush of a fresh apple. “I used to imagine those sisters as my own.”

“Of course you did,” Sister Frances chimes in. “You had none yourself, so you found them in books.”

By the time she arrived at Sabbathday Lake, Sister June’s “natural family” had dwindled to a few cousins, and her love for reading only grew. An erstwhile traveler — with her mother as companion — she recently tore through Alexander McCall Smith’s mystery series set in a Botswana village, and this week she’s been reading about volcanoes.

“She is obsessed with volcanoes,” marvels Brother Arnold, who says he hasn’t much time to read anything but cookbooks. (His most recent page-turner: Pressure Cooker Perfection.)

“I get on these jags,” says Sister June. She smiles again, glancing around the table at her adopted family. “I don’t know why.”

[cs_drop_cap letter=”I” size=”5em” ] can guess why: Sister June likes to learn. It’s the Shaker way. Anyone who pictures the “last living Shakers” as three relics washing clothes on a rock, then taking a break to speak in tongues, couldn’t be more wrong. Unlike the Amish, with whom they’re often confused, Shakers never rejected the outside world. They took to the markets, selling everything from garden seeds to house furniture. Until the mid-20th century, Shaker postmasters (usually women) ran the Sabbathday Lake branch of the U.S. Postal Service. And when little Frances was exhausting her teachers at the schoolhouse in the 1930s, her classroom included a teacher and some neighborhood children who were, as the Shakers say, “from the world.”Nor did Shakers reject technology. They relentlessly sought more efficient ways to work, and all of their goods, including their famous furniture, were designed for utility and commerce. Unsurprisingly, Shaker history teems with inventions of all kinds: flat-cut broom, circular saw, wrinkle-resistant cloth, automatic spring, and the first patented washing machine. If the iPhone had debuted in 1900, the Shakers not only would have been early adopters, they’d have designed apps. The first automobile in Alfred, Maine, appeared in the driveway of a Shaker community that eventually merged with Sabbathday Lake. Shaker entrepreneurs made a killing at the turn of the last century processing medicinal herbs — their “Shaker Tamar Laxative” pill was a runaway bestseller.

Sabbathday still lifes: scenes from around the Shaker village.

The three remaining Shakers are still equally open to the world, with a continual influx and outflow of friends, relatives, and other visitors. “We inherit each other’s families,” Brother Arnold tells me. “Even the dead Shakers’ families keep coming back.” Sister Frances loves to write letters and manages much of the correspondence. Brother Arnold leaves home occasionally to give talks on Shaker history. His techno ringtone goes off every few minutes (“Gotta change that,” he mutters, “I don’t like it”), and he calls his mother in Arizona every day. Sister June has embraced her housemates’ families, including Sister Frances’s niece, who works in the kitchen.

In short, the daily concerns of this trio look very much like ours, except for their extraordinary fidelity to a religious tradition that few “from the world” understand.

[cs_drop_cap letter=”L” size=”5em” ]ike a long marriage, Shakerism requires love, patience, and deep, sometimes difficult commitment to the daily work of living a Christlike life. Adherents experience an almost marital ebb and flow of desire, contentment, and connection. According to Brother Arnold, “the first six months are euphoric. You believe nothing could ever go wrong.” But then routine sets in, the quotidian reality of work and worship and communal living that leads inevitably to times of doubt. How could it not? How can a human being continually adhere to what Brother Arnold calls “an inner prompting, or whispering of the Spirit?” The solution to those occasional dark hours, he believes, is to dig deeper into faith, to refocus and recommit.Back in the dining room, he spreads his hands on the table as we talk of doubt. “If you can’t look at Christ as your lover, then you’re not going to make it.” His expression takes on a somber intensity, and it occurs to me that the marriage analogy is apt. “You’re married to God,” he says.

Sister June, for her part, confesses no doubts, perhaps because she came to Shakerism in middle age. Nor does Sister Frances have misgivings about her choice, though she recalls times in childhood when she “wanted to be anywhere but here.” In the winter of her life, she finds joy in the little things: the kitchen where she spent so many fragrant hours, the mushy novels of Nora Roberts, the shameless indulging of Sam the cat, whom Brother Arnold calls “the only overweight feral cat on earth.” She’s a writer, too: her compendium of comfort-food recipes, Shaker Your Plate, includes lively profiles of Shakers past, and her memoir, Growing Up Shaker, charmingly recounts her rebellious coming of age in the care of Shaker Sisters.

As the three believers share their stories, my eyes are sometimes drawn to the Shaker portraits surrounding us. The current Shakers lace their tales with mentions of their predecessors — some of whom they never knew — as if they were still here with us. Brother Ted, the effusive mentor; Sister Minnie, who made the best molasses cookies; Eldress Prudence, who had a knack for talking to children; Brother Delmer, who planted the apple orchards. It’s like a conjuring trick, calling down their memories to fill these beautiful, empty chairs.

Even Mother Ann seems curiously present tense. Was it really as far back as 1774 when she came from England to America to escape persecution? Shaker lore includes a hair-raising tale of Mother Ann’s two-week confinement in a stone cell so small she could neither stand nor lie down. As they fanned out to establish communities in New England and the mid-Atlantic, early Shakers met with similar hostility from settlers who were threatened by the singing, ecstatic dancing, and speaking in tongues from which the “Shaker” nickname derives.

In only one place did Shakers in America escape contempt: pre-statehood Maine.

“Mainers are rugged people,” Brother Arnold opines. “They knew what it meant to be isolated. To be poor. To go through devastating times.”

Perhaps it was inevitable that the last holdout of Shakerism would be in the Pine Tree State. In any case, the Shakers’ Pentecostal practices died out at the turn of the last century, when their worship became quieter, more inward, and, in Brother Arnold’s opinion, “more meaningful.”

[cs_drop_cap letter=”W” size=”5em” ]orship on this summer morning is quiet indeed. We’ve finished talking. After the full Sister Frances victory tour of the kitchen (“Look at this arch kettle! I burned my dress on it once! Look at that bread table! It’s the oldest artifact in the village, 1790s!”), I ask to join their pre-dinner devotions. In the dining room, Brother Arnold hands out psalters bound in dark-red hardcover, then leads two brief responsorial psalms. Sister Frances sits high and straight, her psalter resting flat on the table, her voice young. Sister June leans forward, cradling her book as if it were an injured bird she found in one of the fields. Brother Arnold wraps things up with an improvised prayer, thanking God for the usual things — faith, fellowship, divine gifts — and asking him to “bind us up as one heart.” He closes with what I interpret as either a wish, a hope, a certainty, or a cry from the abyss: “We ask for competent vocations to be brought to this way of life, so that Shakerism will endure in this place we so lovingly call Chosen Land.”Will it happen? Will “vocations” come? “We cannot see into the mind of God,” Brother Arnold tells me later. “If there are folks who are called, they will join us. This was the feeling of our First Parents who experienced the same thing when they came to America, and then converts ‘came like doves.’ We sincerely believe that if this is God’s work, then he will send vocations to sustain this community. And it is our deepest hope and prayer that they will come soon.”

We close our prayer books. “Shall we sing?” asks Brother Arnold. They launch into “Simple Gifts,” a song I know, a song everybody knows from weddings and funerals out here “in the world.” They sing movingly, convincingly, and I’m flooded with awe and sadness. Their number is so small; their faith is so big.

Brother Arnold turns to me with a penetrating gaze that recalls that tenacious teenager who wanted to be right. It’s more than that now; he wants to be understood. “We’re ordinary people who chose a different way of life,” he says. “We didn’t come here thinking we had the corner on divine light.” He glances at his Sisters. When he says “we,” he clearly means not only them but all the Shakers who came before. “We embraced our humanness. We knew we were broken, and we were looking to be fixed.”

The Sisters nod, smiling at their Brother, and I’m struck by the diverse paths that led these very different souls to the same life-altering leap.

“We have little in common,” he says. That gaze again. “Except for the biggest thing of all.”

This story originally ran in October 2014. Sister Frances Carr passed away in January 2017.